This post is also available in: Italian

Sometimes a departure is a beginning and an ending. Sometimes a departure is unexpected, unplanned, unwanted. Sometimes a departure isn’t solely your own. Sometimes you see the train leaving the station in someone else’s eyes.

With each book, I depart on a new journey. I’m merely a passenger with no ticket in hand. I don’t know where the journey will take me. I don’t know how or when it will end. All I know for sure is that each new book asks the impossible of me: to begin again, to depart for parts unknown with those familiar traveling companions—doubt and faith and fear. And each book’s point of departure varies in all ways but one: The beginning often appears out of the blue—an open car door, a memory, a line of poetry, a surprising or surreal or resonant image, a photograph I keep returning to, a “Partenza” sign at the Milan airport…

A few summers ago after flying to Milan, I found the seeds of a new book. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that this happened in Italy, a place that inspired the very first photography book, The Pencil of Nature. However, the visual source of my inspiration wasn’t the picturesque Lake Como as it was for Henry Fox Talbot, but another, more commonplace body of water—the workaday Po River, the country’s longest river. Flowing through the agricultural valley that bears its name, the Po nourishes those prized fields of rice from which risotto is made.

Crossing the Po River, I thought of Luigi Ghirri and his series of photographs of this farmland he called home. In this late project, he was drawn to mystery and loss in the landscape, and, fittingly, he left behind a mystery of his own: a last roll of film from his series about the decaying houses and fertile fields of the Po Valley in this northern Italian province where he’d lived most of his life, a roll he’d left undeveloped when he died unexpectedly in 1992 of a heart attack at his home in Reggio Emilia. I like to think of these final images as a kind of farewell—including this one of a man vanishing into the fog—especially when paired with these words he wrote near the end of his life:

“…in the end all we can know, tell and represent is but a small crack on the surface of things of the landscape…in which we live.”

And in which we love, I would add, for Ghirri, a former land surveyor, was also charting a kind of geography of love: “I have viewed these places with a gaze full of affection and love, in an attempt to perceive a simple and astonished feeling of belonging.” We accompany Ghirri through the departure point of his gaze, and, pieced together, his photographs form a kind of “imprecise cartography…of our impossible landscape, with no scale and no geographical order to orient us.” Yet perhaps it’s the very nature of this disorientation itself—this blurring of lines between interior and exterior landscape—that also, paradoxically, guides Ghirri and all of us who follow in his footsteps:

“[This] tangle of monuments, lights, thoughts, objects, moments, and analogies form the landscapes of our minds, and we seek them, even unconsciously every time we look out of a window at the great outdoors, as though they were points on an imaginary compass showing us a possible direction,” Ghirri noted.

For the past few years, I’ve often thought of Ghirri’s Po Valley work while revisiting the Midwestern farmland where both my father and I were born and where his Quaker family lived for generations, with its foggy floodplains rich with memory and poetic associations. As a child in this rural Indiana county, I’d sometimes accompany my country doctor father on house calls to farmers with newborns he’d delivered—as well as to Todd’s Funeral Home to say farewell to one of his patients. Unfortunately, all that remains of these road trips is a photo I took of my father, one faded Polaroid—so cloudy all that’s left is sky, and the faintest outline of his physician’s black bag. And my 96-year-old father is fading as well. With this cloudy Polaroid as my guide—and my father’s and my memories as my emotional road map—I’ve begun to retrace some of his house calls through the cornfields and small towns of Rush County. I work predominantly at night and in the early morning—when most people come into the world (my father delivered some 2,000 babies) and most people leave it. That’s also when memories are woven, according to Walter Benjamin, when “remembrance is the woof and forgetting the warp.”

Before departing for my first trip, I reread Paul Valéry about the mystery of beginnings, which led me to revisit a particular ending before falling asleep, “Fallen Apples,” the final photograph of My Dakota: “The opening line of a poem is like finding a piece of fallen fruit you’ve never seen before. The poet’s task it so create the tree from which such a fruit would fall.”

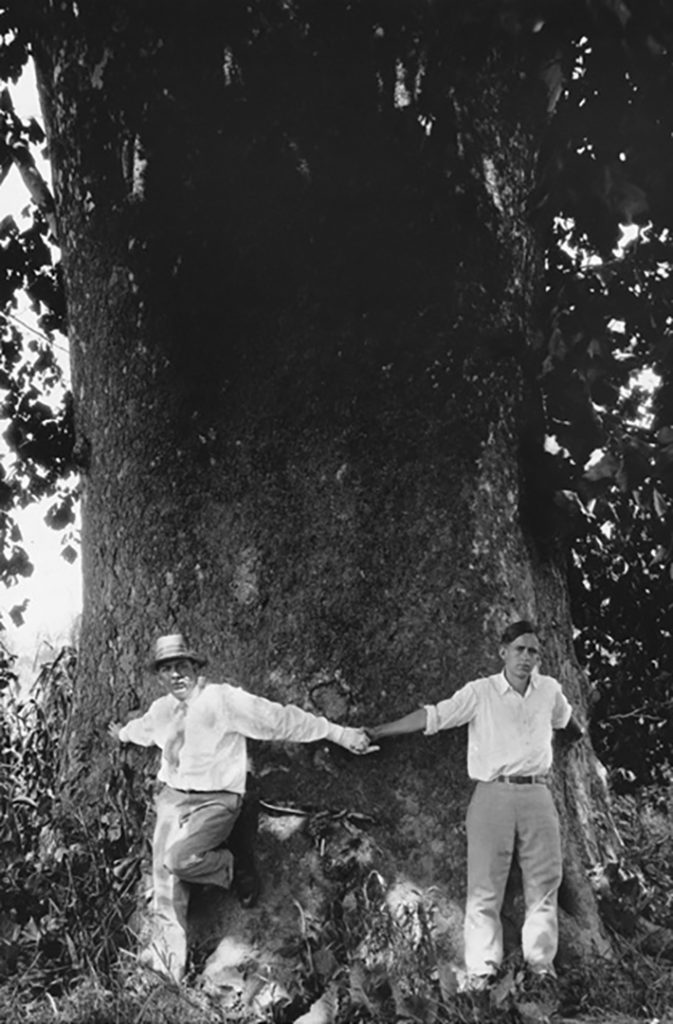

Sleeping fitfully, I dreamed of the largest sycamore I’d ever seen—except in an old photograph taken near the rural region where I was born—a tree that seemed to be a landscape in and of itself.