This post is also available in: Italian

John Berger has been very much on my mind since he died early January. Some say a light has gone out of the world. Gone, I wonder, or merely shifting?

Each cloudless, wintry afternoon, I watch the same light slowly climb my bookcase in our house overlooking Wellfleet Harbor on Cape Cod. At sunset, the light rests on the top shelf of books—Here is Where We Meet, A Fortunate Man, Ways of Seeing, and the other Berger books in my late father-in-law’s vast library—glowing red for one surreal moment, before fading.

Preparing to travel to Italy this spring, I’m reading a passage about Giorgio Morandi’s way of seeing that Berger wrote some sixty years ago:

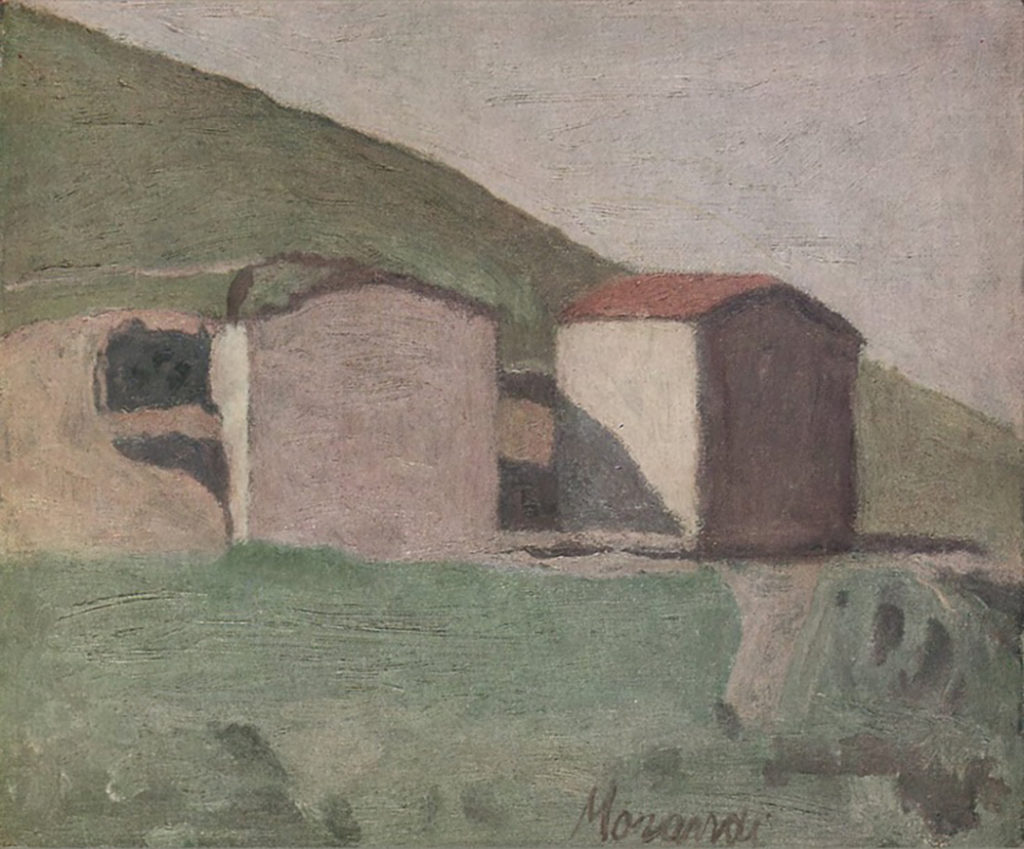

“A contemplation so exclusive and silent that one is convinced that nothing else except Morandi’s cherished light could possibly fall on the table or shelf…[the painter] allows the same light to fall on his few precious, eccentric possessions as falls on Italy outside.”

For more than twenty years—ever since my first visit to Italy—I’ve been drawn to Morandi’s paintings. The poet in me delights in how his still lifes sometimes rhyme with his landscapes. In these two paintings, for instance, I love how the square bottles echo the square houses—and how their muted palette and soft light also rhyme. And the more intently one gazes, the more this row of bottles seems to be a landscape in and of itself. It’s as if Morandi’s still lifes, taken together, chart a kind of map of the painter’s own imaginative landscape: a soft-hued, spare, yet richly contemplative world illuminated by his meditative gaze (Berger calls it “monastic”) and lit by same subdued light as falls on his beloved Bologna, the home he rarely chose to venture far from. Ultimately, perhaps what I’m trying to describe is art’s imaginative borderland—that poetic space where the painting or photograph or symphony exists between an artist’s inner landscape and the outside world he or she inhabits, all lit by the same light.

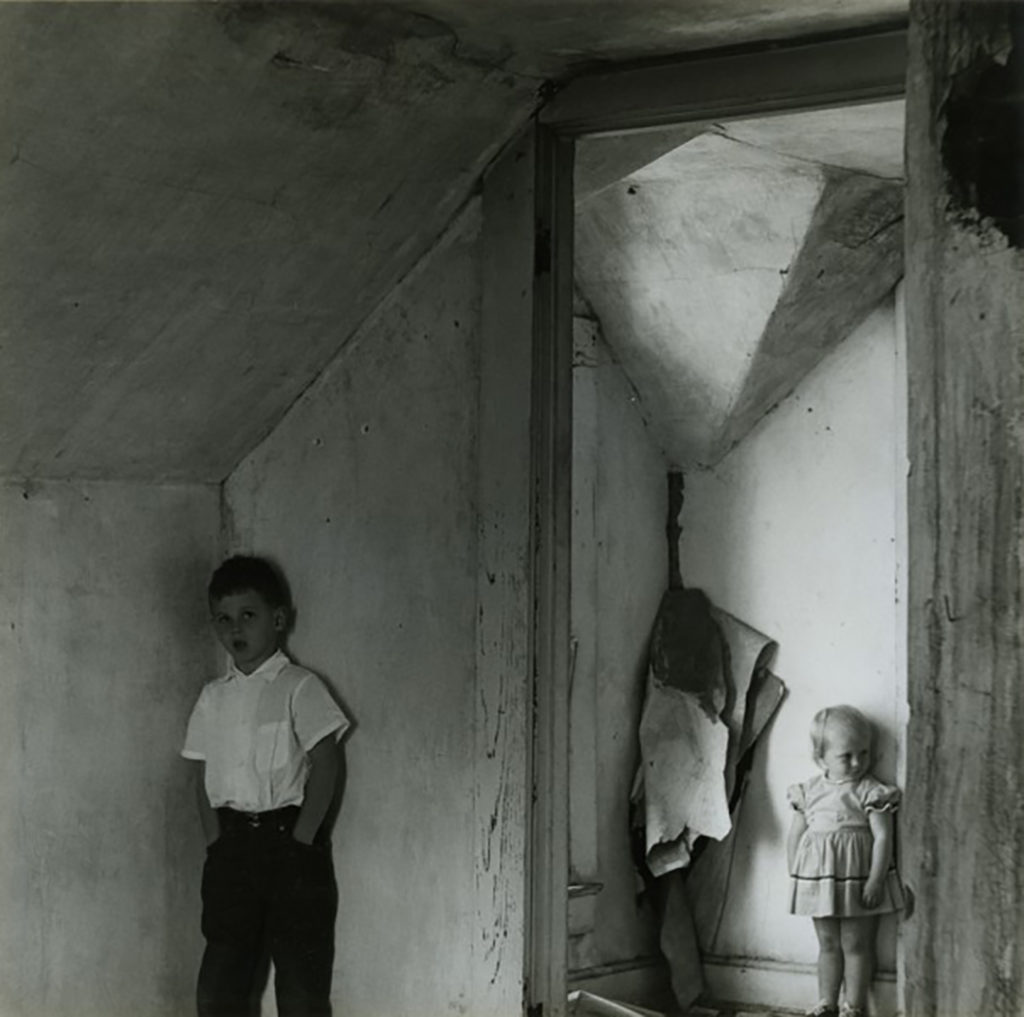

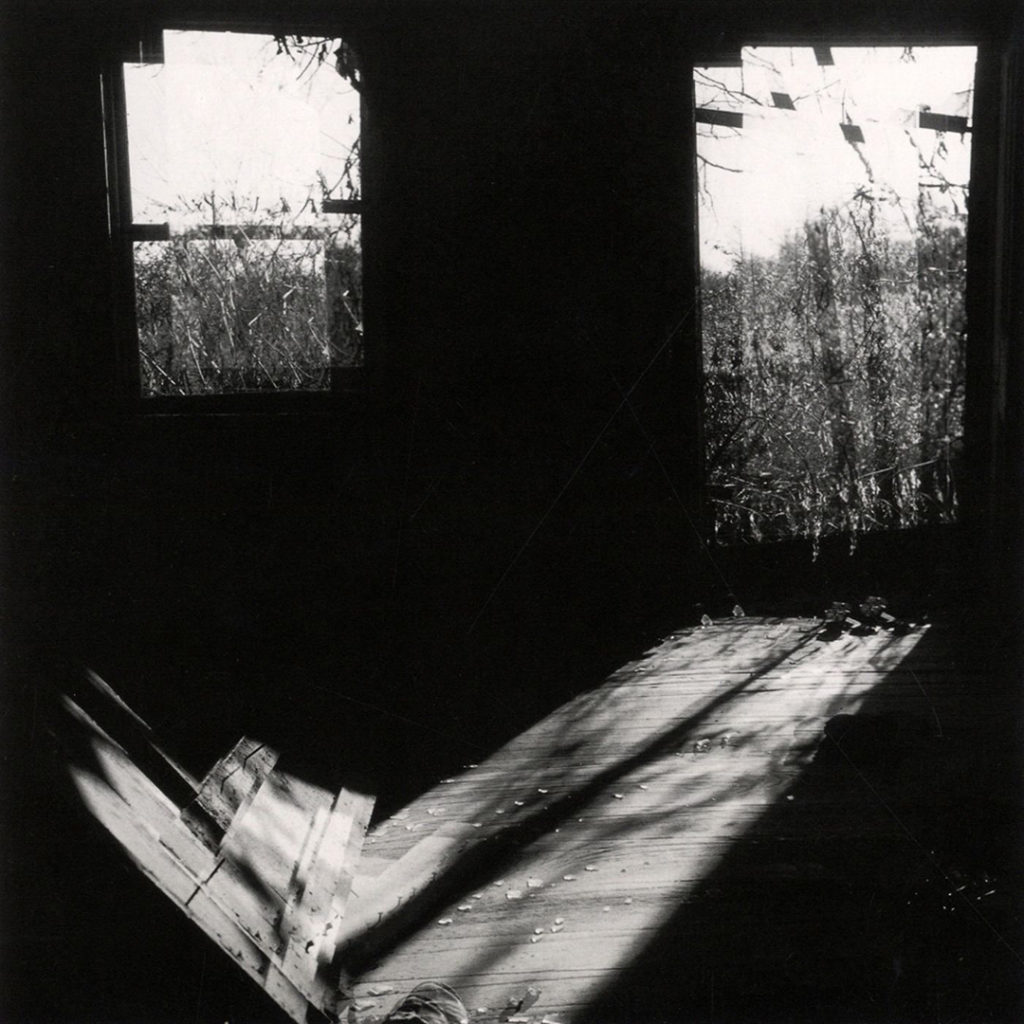

So, it makes sense that it often takes a poet—or fellow artist in the same discipline (Berger was both a poet and painter as well as an essayist and novelist)—to understand another artist’s imaginative borderland, to chart its particular geography, metaphysical weather patterns, and play of light. A deep friendship can also be illuminating. The poet Guy Davenport once wrote about his friend, the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, both of whom lived in Lexington, Kentucky:

“I have watched Gene all of a day wandering around in the ruined Whitehall photographing as diligently as if he were a newsreel cameraman in a battle. The old house was as quiet and still as eternity itself; to Gene it was as ephemeral in its shift of light and shade as a fitful moth.”

As the last light dims, I reach up to switch on my reading lamp. Content to be home after a hectic fall of too much transatlantic travel, I recall something Igor Stravinsky once told his friend, the American conductor and writer Robert Craft, about the secret of sleeping soundly anywhere in the world, no matter how alien the hotel room or how far flung:

“I am able to sleep at night only when a ray of light enters my room from a closet or an adjoining chamber.”

The Russian composer called this familiar light his “umbilical cord of illumination.” It reminded him of the street light outside his bedroom window on the Kryukov Canal in St. Petersburg where he grew up:

“[This same light] enables me, at seventy-eight, to re-enter the world of safety and enclosure I knew at seven or eight.”