This post is also available in: Italian

T.B. How did you start to be interested in photobooks as an editing expert1/photographer2?

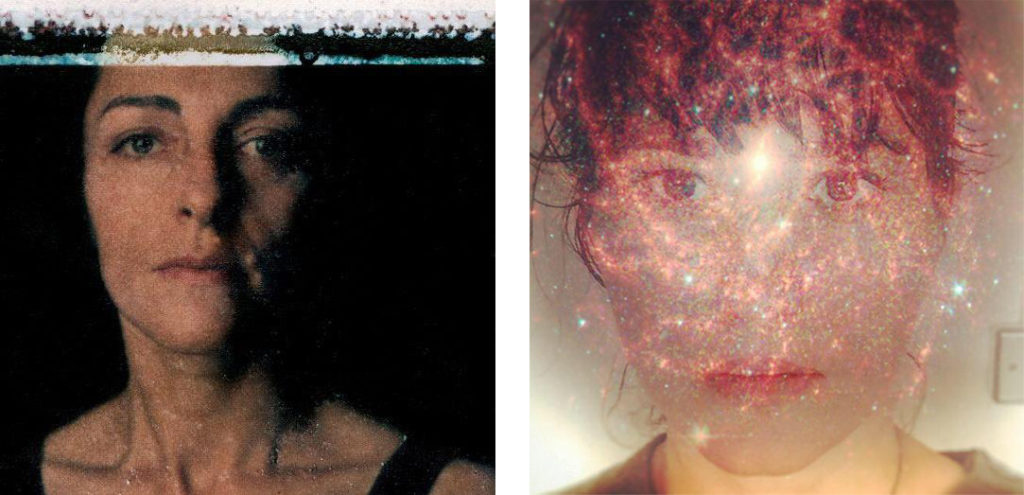

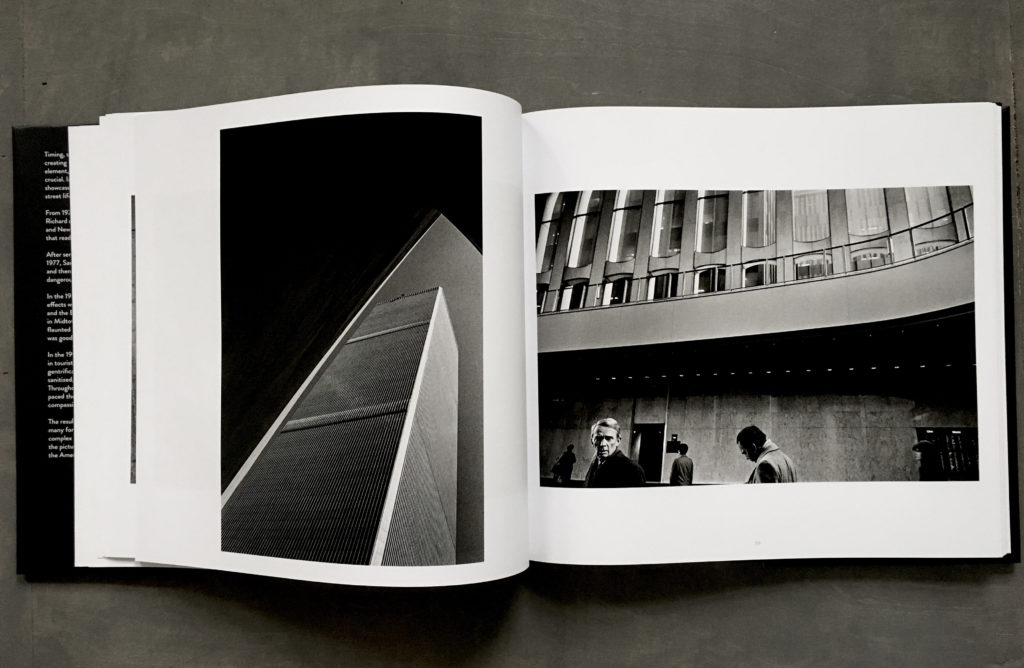

R.M.1 It happened organically, having spent the last 30 years working in the medium in various capacities. I have always been interested in the juxtaposition of images. Editing a body of work provides this opportunity. I embrace the fact that there is a responsibility in pairing images. I dreamt of being a film editor and have a passion for cinematography which has informed both my work as a photographer and as an editor. It seems to have come full circle with my work editing long-form narrative.

Richard Sandler, photographer: “Régina helped me immeasurably edit my book, The eyes of the city. She loves editing pictures… she has a superb photographic memory and that was very important, because my book covered 24 years of work. So that when we made page spreads she remembered associations between pictures, many of which made it into the book. The best thing that Régina does is create a free and intelligent space for editing; thus, her dedication to excellence informs the process, bringing the photographer’s vision into a clearer focus.”

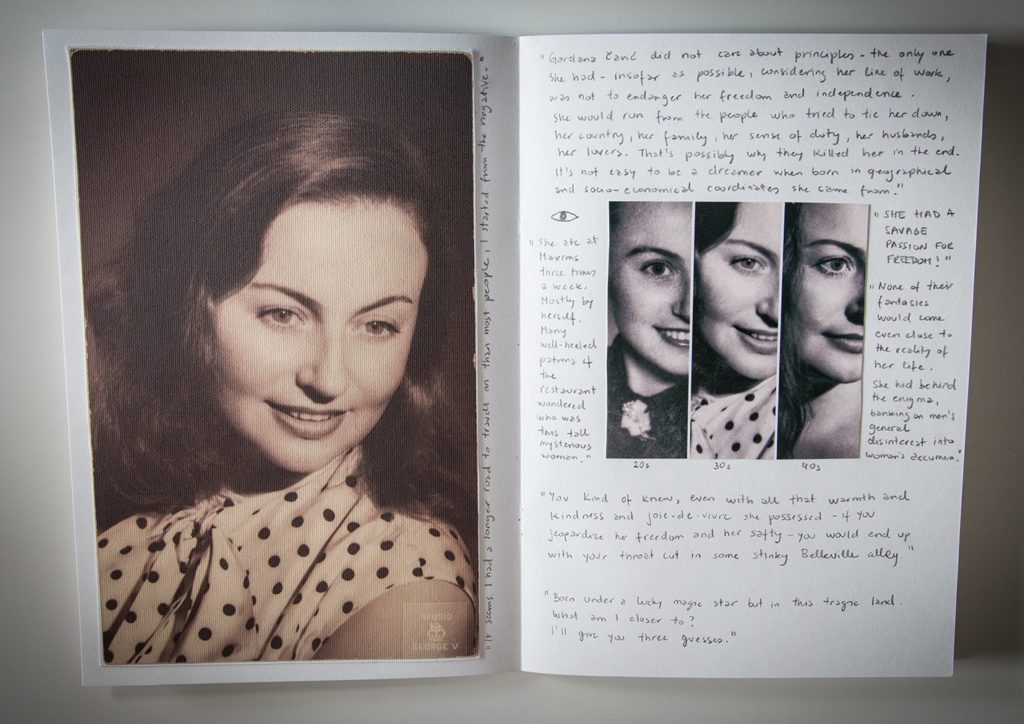

D.J.2 I was an avid comic book reader and a collector from early childhood. So it was a natural progression to photobooks. I still prefer graphic novels to photobooks; I have to admit. This might explain why the relationship of image and text is pivotal in my work. Sometimes I get frustrated with the sheer number of photobooks being published every year. Many of them seem to me a very expensive and an unnecessary exercise. But when they are good, they are fantastic.

T.B. What was the first photobook you loved and why?

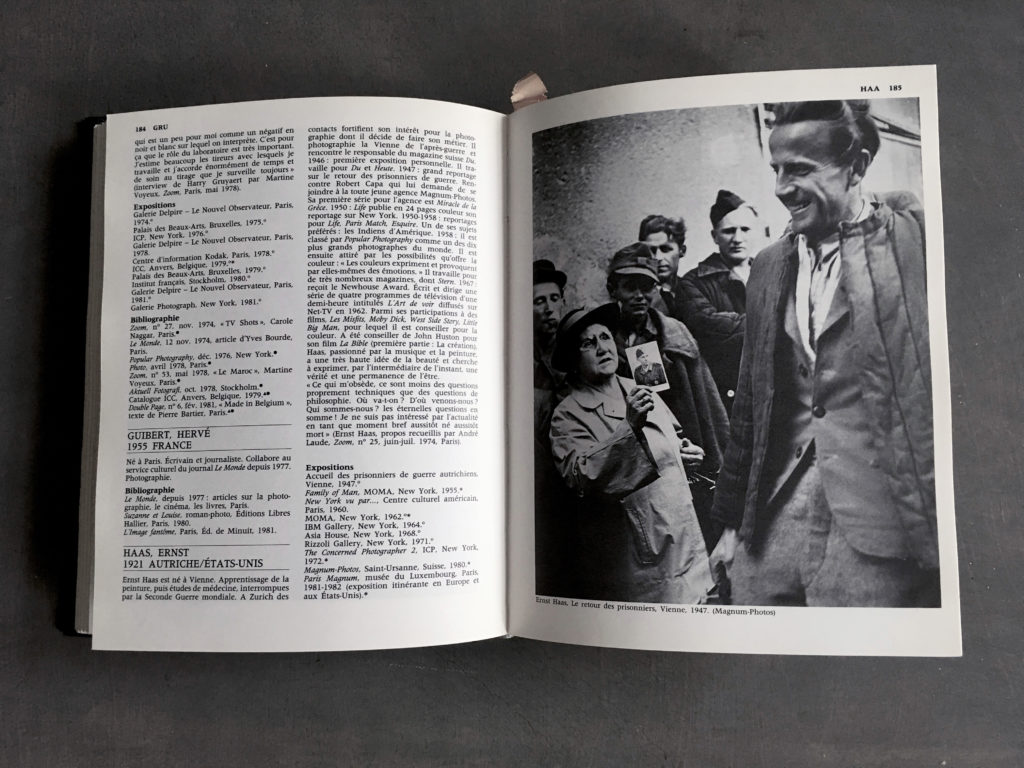

R.M. It wasn’t a monograph, but a Dictionnaire des Photographes compiled by Carole Naggar. I spent many hours perusing through it, it provided quotes and biographical notes which provided a window into the photographers’ personal journeys and approaches and in most cases a visual.

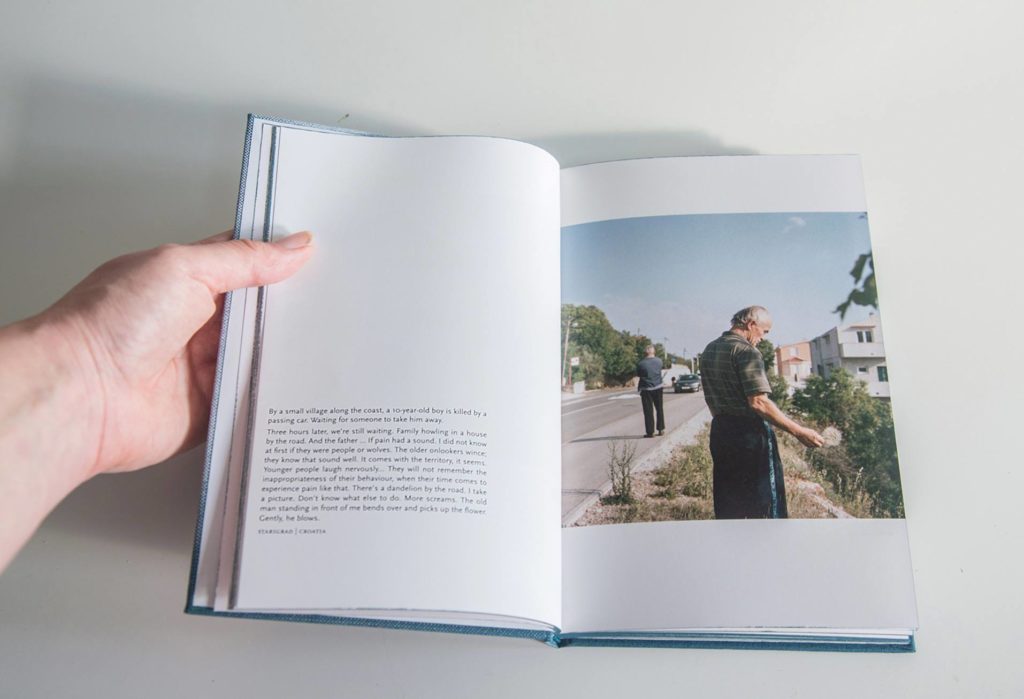

D.J. The first book that kind of broke my heart was Masahisa Fukase’s Karasu or Solitude of Ravens. It is so desolate and alienating, you feel like you are inside the author’s head; and it’s not a pretty place to be. At the same time you are fascinated that a book has this power to suck you into a parallel world where you inhabit the mind of a very troubled man, and it takes you on a journey with him through a Japanese winter, with black birds everywhere – like a bad omen of what was to happen to Fukase later on. I think my first serious body of work Seeing Things was heavily inspired by Solitude of Ravens.

T.B. Do you believe in the power of photography and photobook? Do you think it can help and how in these dark times we are living in?

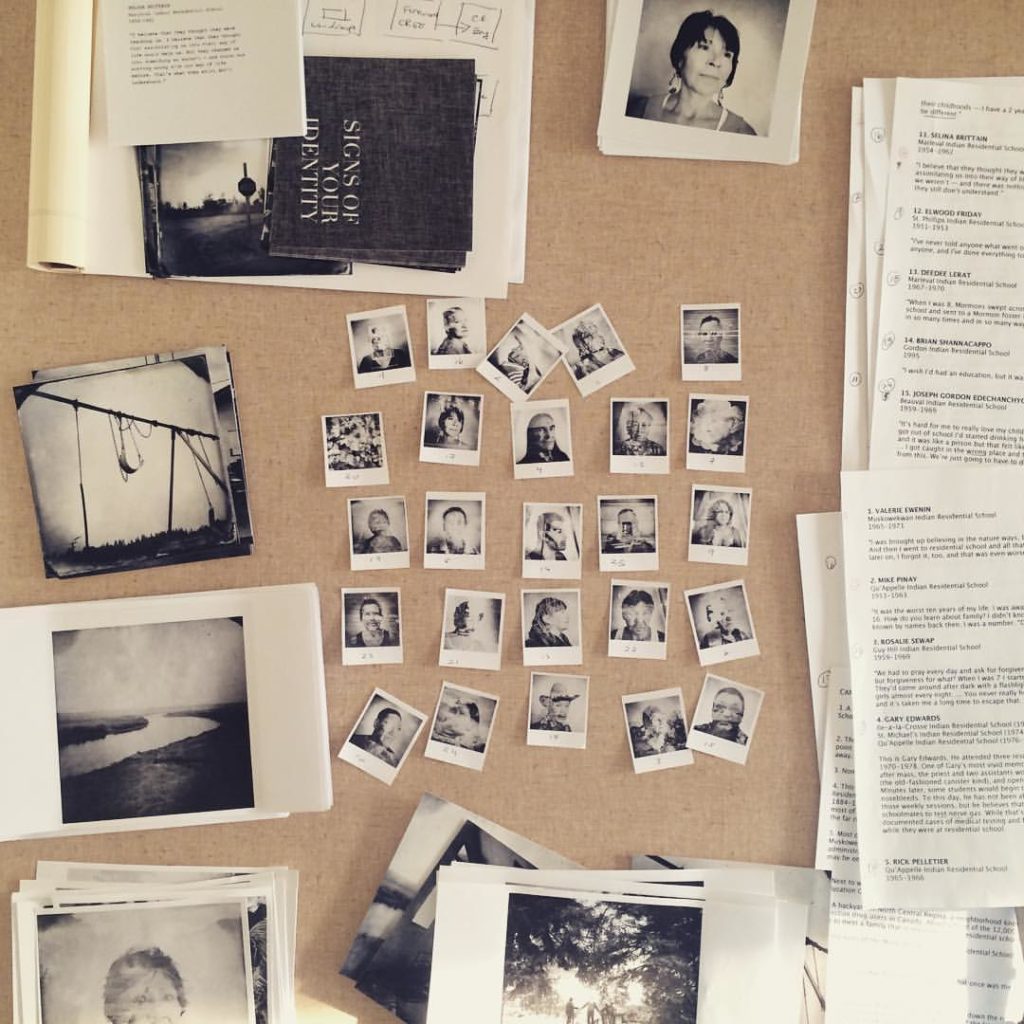

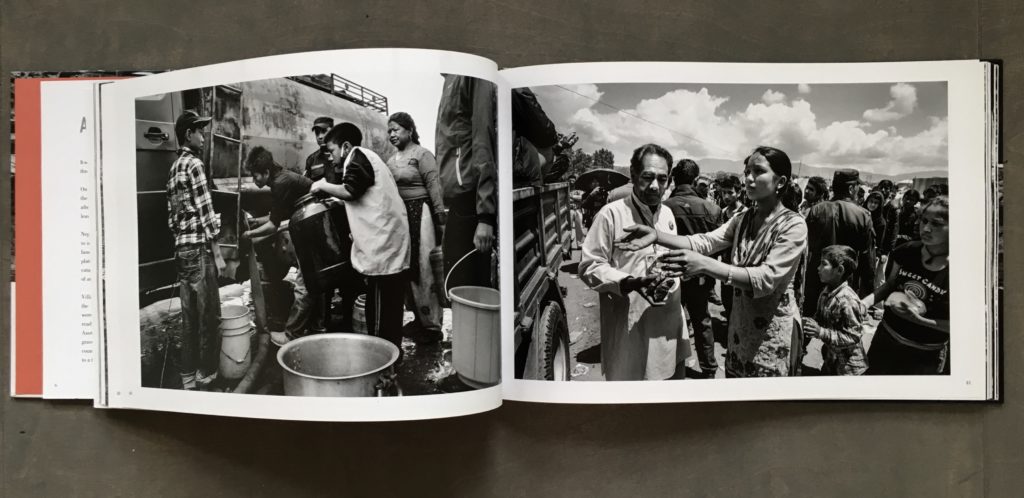

R.M. We would not be speaking today if I did not. A body of work gathered in book form becomes an object with a life of its own. I enjoy working with long-form narratives, sequencing and articulating a story. I have edited a number of books for FotoEvidence Press, that is dedicated to photographers whose work focuses on exposing social injustice, violation of human rights and assault on human dignity. The resulting books serve as enduring testimonies and activism tools.

D.J. Photography in general, yes, it has a power to challenge, inform, provoke, etc. We know historical examples of many images that started serious discussions or reactions to what they were showing us, the audience. However, the reality of the photobook publishing is that on average 500-1000 copies of the book exist. These are small numbers to have a major impact on challenging or enlightening an audience. But these photobooks can exist beyond a physical object. For example, my book YU: The Lost country provoked a significant reaction online. The review in The Guardian was shared more than 5000 times, my interview with BBC World was heard by hundreds of thousands people, etc., so it lived far beyond 500 individuals who purchased the book.

T.B. Who is a contemporary photographer you love and why?

R.M. I don’t have a “favorite” photographer. I do however admire and respect a number of photographers who have distilled in one single image all there is that personally moves me in humanity.

D.J. Uh, there are too many, it’s a very difficult question to answer. But, I have to tell you about a contemporary artist that absolutely blew my mind. I was showing work in DOCfield Barcelona in summer 2016, and my friend, a brilliant Bangladeshi photographer, Sarker Protick, also happened to be in town. So we met up and went to see Andrea Fraser exhibition in MACBA. It was absolutely amazing. The scale, her critique of art institutions, her humor and complexity of her work is incredible. Fraser’s photographic series White People in West Africa really made me laugh at loud. At the same time it was an excellent commentary and reversal of roles from the usual tropes of travel photography.

T.B. Do you think we need photobooks as object, because we live in a very virtual way? What is the point of printing on paper today?

R.M. One of the challenges of photography is to translate our multidimensional reality onto a two-dimensional plane with eloquence and grace. A book is three-dimensional by nature, it can be held, felt, looked at, put down and revisited, hopefully each time offering a new experience. It is tangible.

Svetlana Bachevanova, Publisher at FotoEvidence: “Régina Monfort has an eye for photography and a soul for social justice. Over the last seven years with FotoEvidence, Régina edited ten of our books, some of which were among the “Best Photo Book of the Year”, selected by TIME magazine, Smithsonian magazine, Mother Jones and Lens Culture. She is a great editor, a passionate activist and a dear friend.”

D.J. Yes, firstly, people will always fetishize objects, and photobooks are sometimes truly exquisite works of art. Also their price makes them affordable to majority of collectors. Secondly, photographs also look very different when seen backlit on the screen of your computer and when encountered in print. The experience is totally different. I do think we do not need so many photobooks. It seems to be something of an obsession of photographers to try and shoehorn projects that are not meant for the book format into it, and it often really shows.

Régina Monfort is a French-born photographer and editor based in Brooklyn, New York.

www.reginamonfort.com

Dragana Jurisic was born in Croatia. She is currently based in Dublin.

www.draganajurisic.com